Portfolio

Le Grand Cru 1994- 2001, work by Feri de Geus

The identity and idiosyncrasy of choreographer Feri de Geus lies in a good sense of visualizing themes in a juncture. Visionary, non-conformist and reflective. His work is accessible but has an intellectual make up in which both concrete text as abstract dance are naturally connected. Successful productions from the early days of Le Grand Cru are Echo and You’ve got a watch, I’ve got the time.

Around the turn of the century themes became more political and focused on global events. Examples include: Euroblues (1998), a political satire on a united Europe, Beautiful People (1999), which showcases the inability of Europe with regard to the civil war in the Balkans and The Eye and the Other (2001) about four white people with the impending “millennium bug” fleeing to Africa to give their own vision on the black continent.

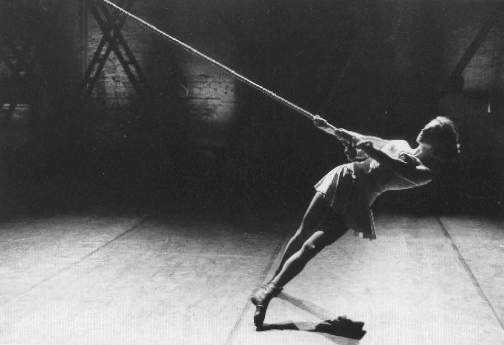

Echo is made as a tribute and requiem for de Geus’ friend and composer Stefan van Campenhout who disappeared in the Swiss Alps in 1993. The performance is a personal reflection of what might have happened to him and what his thoughts might have been during his final hours. In general, the performance is an allegory for every person who faces the loss of a beloved one.

“…To imagine your life as a line, to see the peeks and depths of the course of your own life…this line appears in the shape of a rope on the floor in Echo. It could be a schematic drawing of the mountain range in which Stefan van Campenhout tragically disappeared, but also the lifeline of the composer, a good friend of choreographer Feri de Geus, who needed to create a lot of distance to build a performance with such a universal eloquence. The fact that this line of rope stands for more than the image signifies ads to the richness of meaning de Geus is able to create with different elements of this work. Echo is a summation of movement, text, singing and play. A collection of fragmentary scenes loosely connected but miraculously creating a coherent dramaturgical whole…”

—De Groene Amsterdammer, Marijn van der Jagt

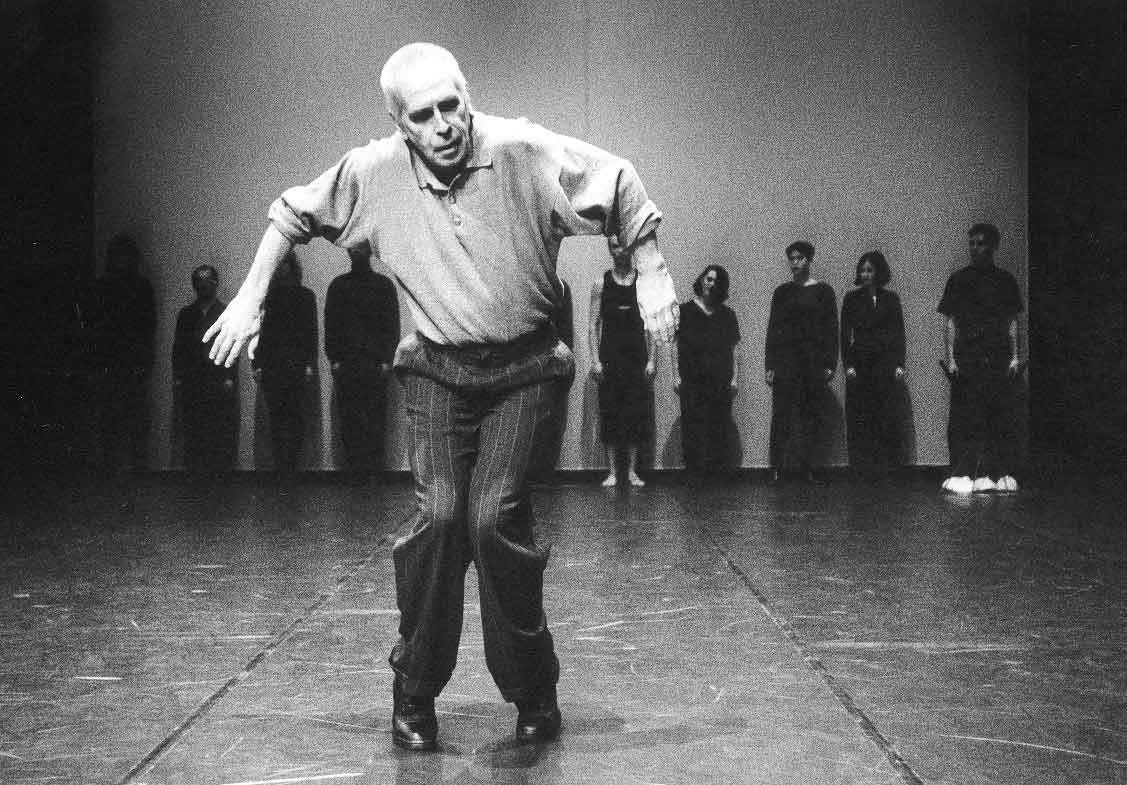

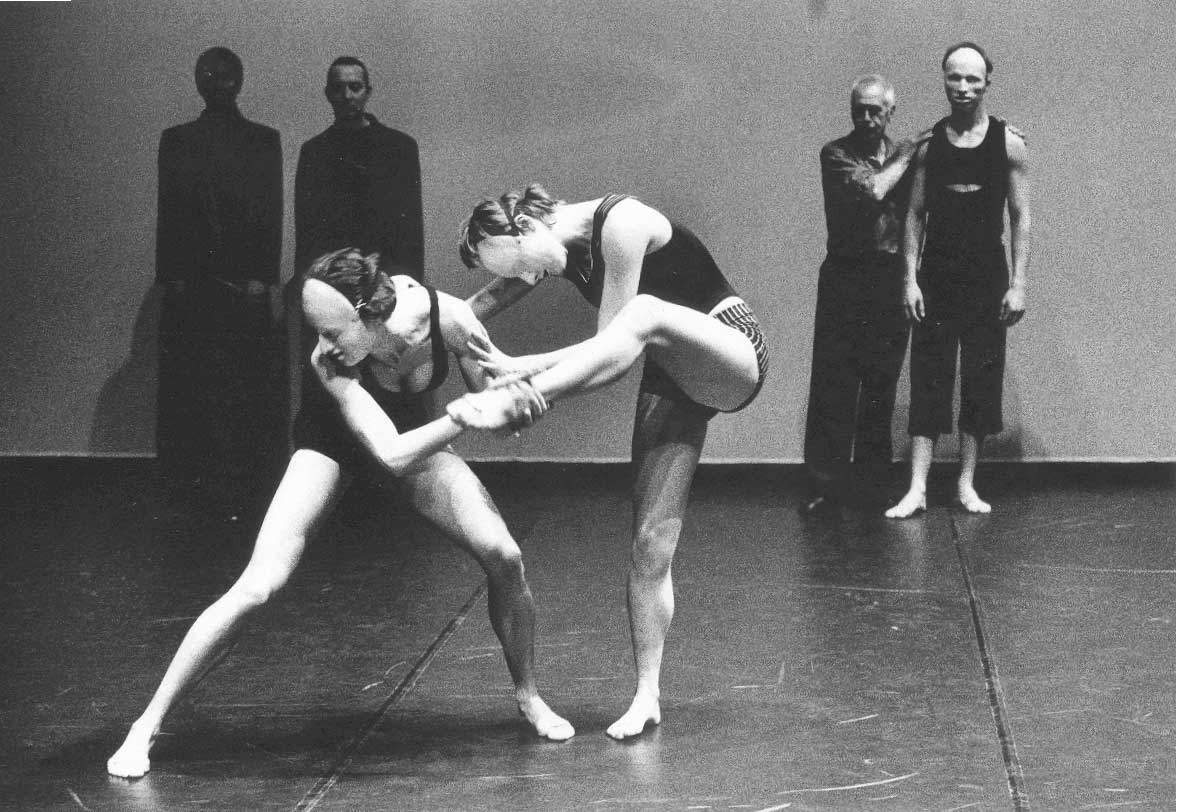

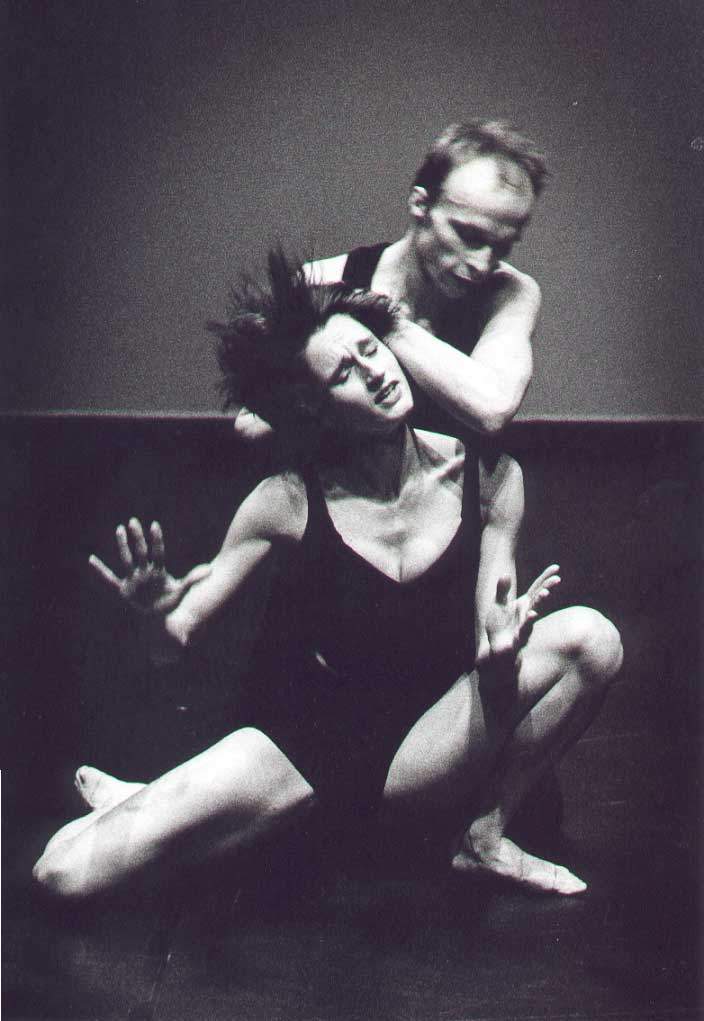

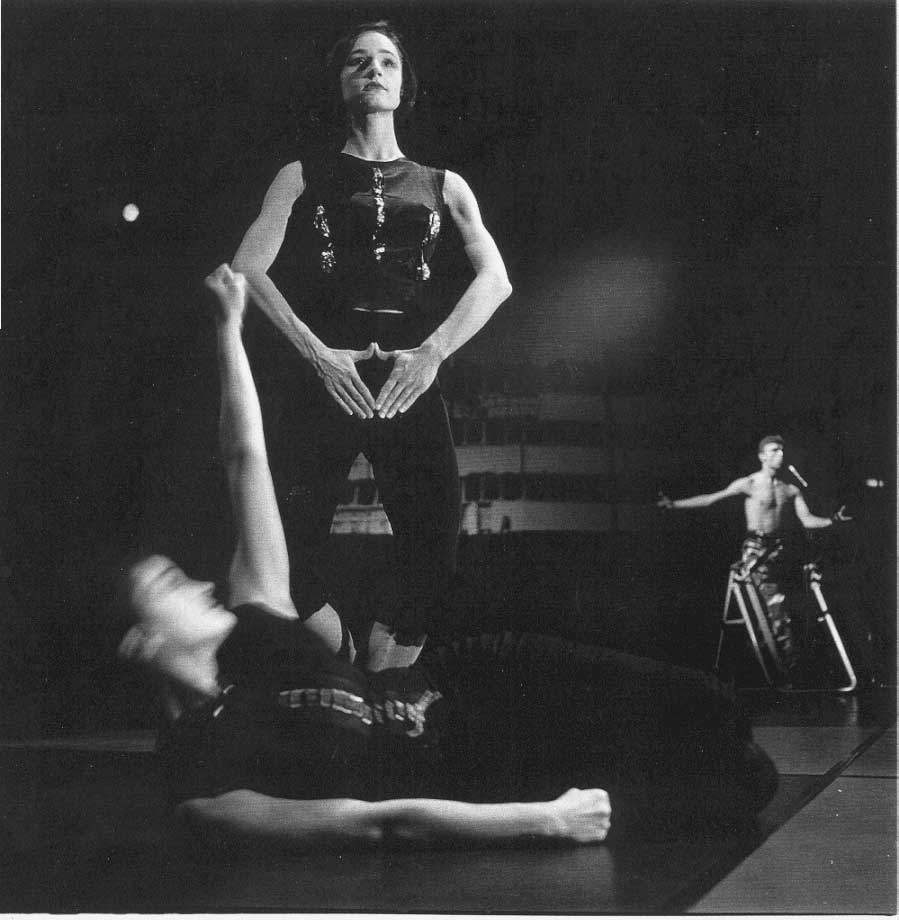

You’ve Got A Watch, I’ve Got The Time is opgebouwd rond drie generaties dansers met vergankelijkheid als thema. Herinneringen, ambities en seksualiteit zijn motivaties die definitief veranderen met het verlopen van de jaren. De dansers zoeken naar betekenis in het leven en worden daarbij gesteund en geleid door een spiritueel a-capellakoor. De 62 jaar oude ‘danseur noble’ Jaap Flier, medeoprichter van het Nederlands Danstheater, maakt met deze voorstelling een bijzondere comeback. De muziek voor koor werd geschreven door de Chileense componist Patricio Wang.

“…De Geus’ love for dance let the body sing…”

“…It is not only the merit of the composer and conductor that makes the choir appear strong and convincing. De Geus succeeds to integrate the ten singers harmoniously into the dance sections.”

—NRC handelsblad, Caroline Willems

“…Finally Jaap Flier intervenes. He gets hold on the younger dancer, cuts him down with his grizzled grimace and glorious steps. But then the unavoidable old age against youth confrontation appears. Against the naked vulnerability of the early youth he puts his tawny torso as a symbol of matured wisdom. It all happens with a breathtaking acquiescence.”

—Trouw, Eva van Schaik

“De Geus communicates his different themes crystal clear, using in an excellent way the different characteristics and qualities of the three generations. The touching second solo of the 62 year old Flier, quiet and well-considered, is in fact the highlight of the performance and with it a warm plea to cherish the elderly dancers.”

—Het Parool, Francine van der Wiel

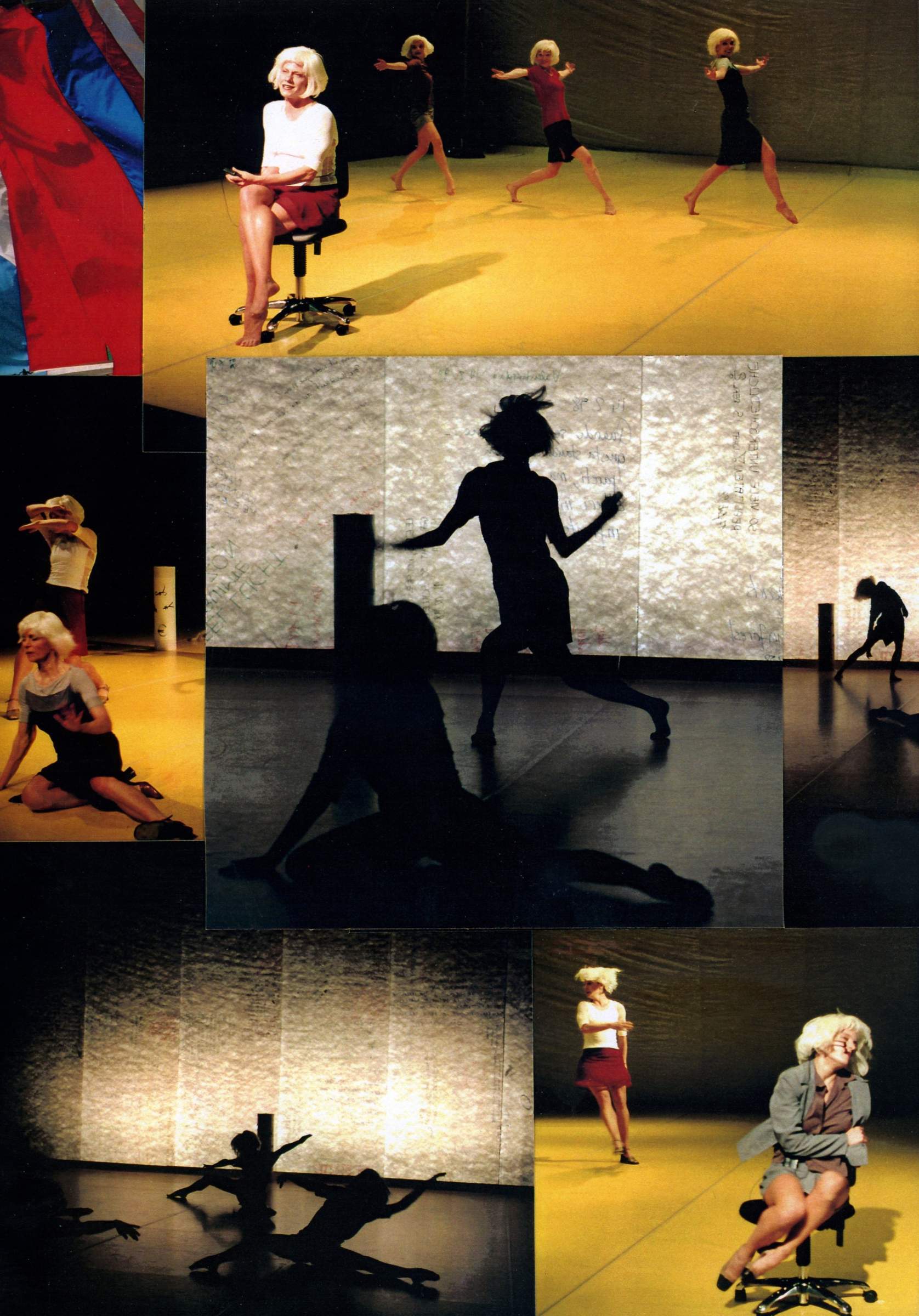

Euroblues is a dance performance about the imaginary as well as the imposed concept of Europe. Feri de Geus reflects on Europe’s situation by using the different cultural backgrounds of the performers. As their language and body are used as text material, borders disappear and individuals shift their dreams drifting into ever growing blurred structures and institutions. How do we react to this alienation? Are we still real or have we become our own icon?

“…Through Internet tunnels they reached (…) Europe, the land of virtual freedom where nor geographic nor moral boundaries no longer exist and all differences have disappeared…”

“For more than an hour they attest to their ‘liberating virtuality’. In short: Euroblues is a superbly cynical production…”

…”The result is a heart rendering blues that goes to the bone that at times sets you off in a fit of laughter, but is delightful to the eye at the same time…”

—Trouw, Eva van Schaik

“…Euroblues, that sense of being alienated from one’s own culture and dissolving into a grey mass, hopefully is a passing fin-de-siècle feeling. In the hands of the director fading Europe is a disastrous decorum. At the end, as a deus ex machina Zeus appears. In the figure of a polish actor the Supreme Being tells us what happened to his former mistress Europe: ‘Suddenly she was gone. In the crowd I sometimes believe I see her. She smiles at me, but it is a frozen smile, an advertisement on a billboard’…”

—NRC Handelsblad, Floris Brester

Beautiful People deals with madness in our time symbolized by the character of Don Quichot, the romantic hero and fool who fights for his ideals. Presented in front of a backdrop of Sarajevo ruins, the performance mostly deals with the insensibility of modern man. Not only of those who make war, but also of those who sit idly by, watching it happen on a screen. The glorification of violence and the lust for sensation in movies and talkshows mingles with real war and real victims.

“Feri de Geus impressively comments on the insanity of the world.”

“…With ‘Beautiful People’, following Euroblues, he again mingles dance, mime, text, film and singing as well and lies his concern in universal topics in a disturbed, burning world…”

“…Magnificent images appear on the screen from the cemetery in Sarajevo, with crows in leafless branches. It is here that two women wander in Zorro-disguise: Don Quichot (Noortje Bijvoets) and Sancho Pancha (Dalia Zaltron). In front of this fresh buried past Don Quichot rides his fitness-machine amongst riddled ruins. In the text of the song The Man of la Mancha (Jacques Brel) Bijvoets spurs her iron horse, but the animal is taken away from her by an anonymous soldier, with a red beret, bare chest, black stripes under his eyes and in camouflage pants (Thomas Falk). By putting Thomas Falk on the stage, De Geus unconsciously says more than by putting the image of soldier Ryan or Karremans alone, because in this outfit Falk is the very image of Rudolf Nureyev, as he was in his portrayal of the king’s eagle under the fallen dance horses, leaving us with a Don Quichot version as well. Through this, for me ‘Beautiful People’ obtained the depth of an art critique on dance art.”

—Trouw, Eva van Schaik

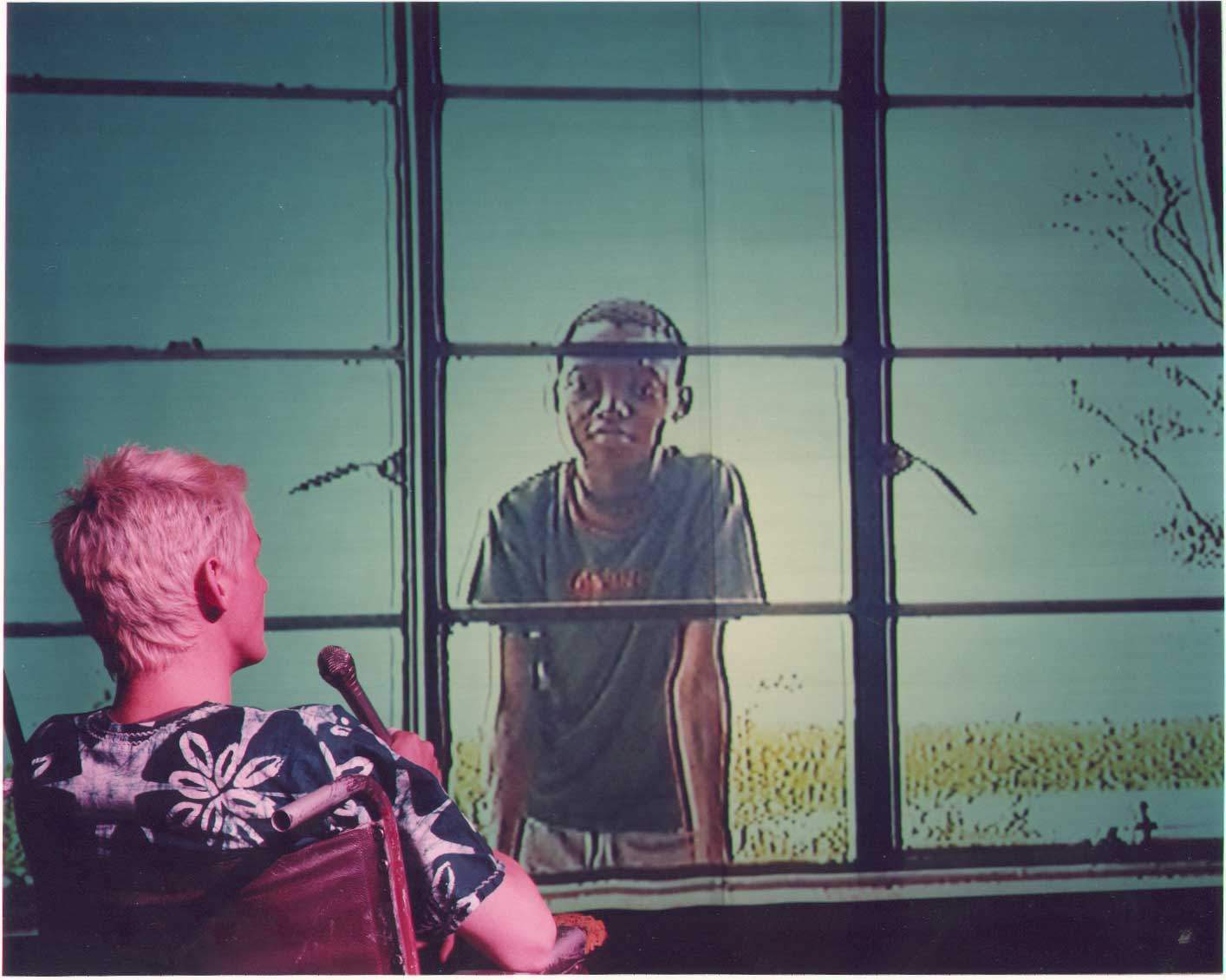

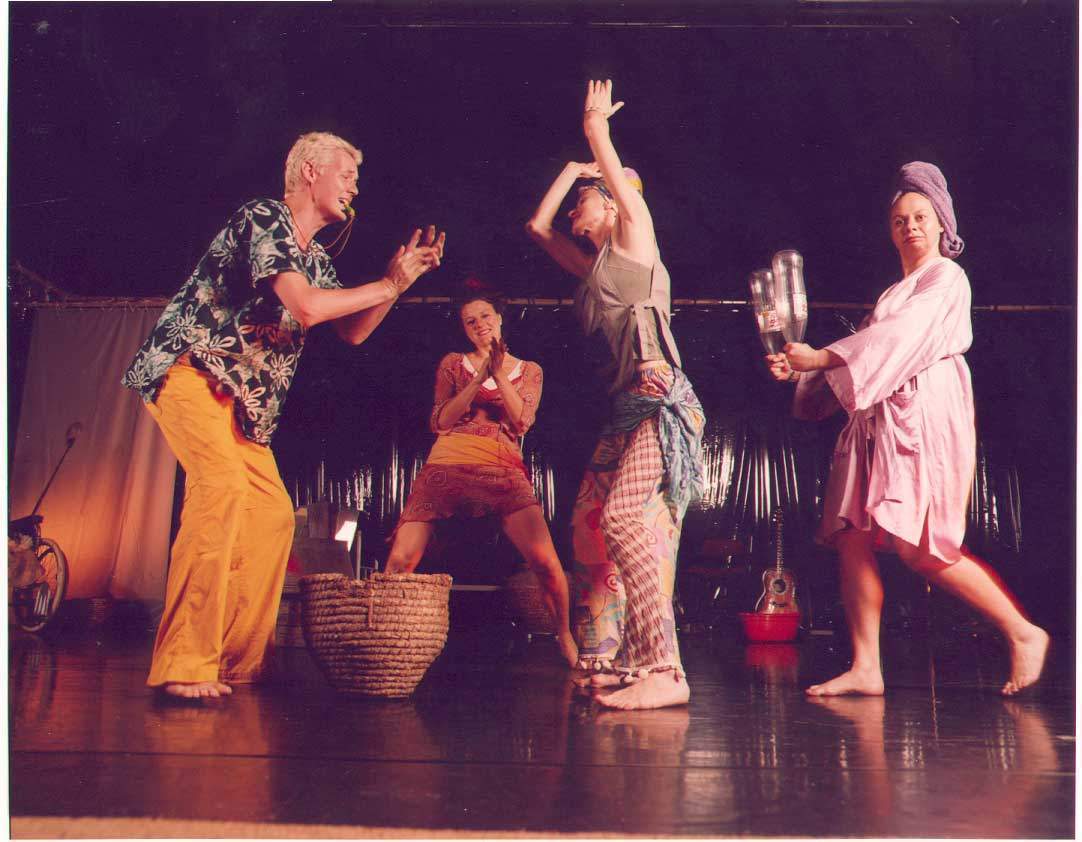

In The Eye and the Other four acquaintances have left their material belongings to withdraw to a country house on the African continent. In fear for a world crisis because of the millennium bug, they have moved to a Third World country. Confronted with each other day and night, they discover that their mutual fear is based on doubts about themselves and how they deal with life. Their personal confessions turn into a psychological dissection table, in which each tries to legitimate one’s own behavior. The world outside, a supposed safe heaven, becomes focus of their frustration in a mixture of missionary and racist reflections.

“…It starts with ecstatic African percussion, dance and singing – stylistic devices that give perspective to the short personal stories that each of the performers displays. By doing so they claim to be connected to African culture, more bad than good obviously, since they are more occupied with their personal well-being and their alleged openness to others. ‘Het Oog en de Ander’ rests on its biting sarcasm through which the group members outplay all the deceitful racist prejudices. The staging is direct without distractions. It builds on a direct and lively visualization of the little stories told, which is a typical characteristic of Dutch dance-theatre. At the end, one of the performers paints a skeleton with black paint on his white torso, hanging out of a wheelchair…”

—Gerald Siegmund. Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung